Table of Contents

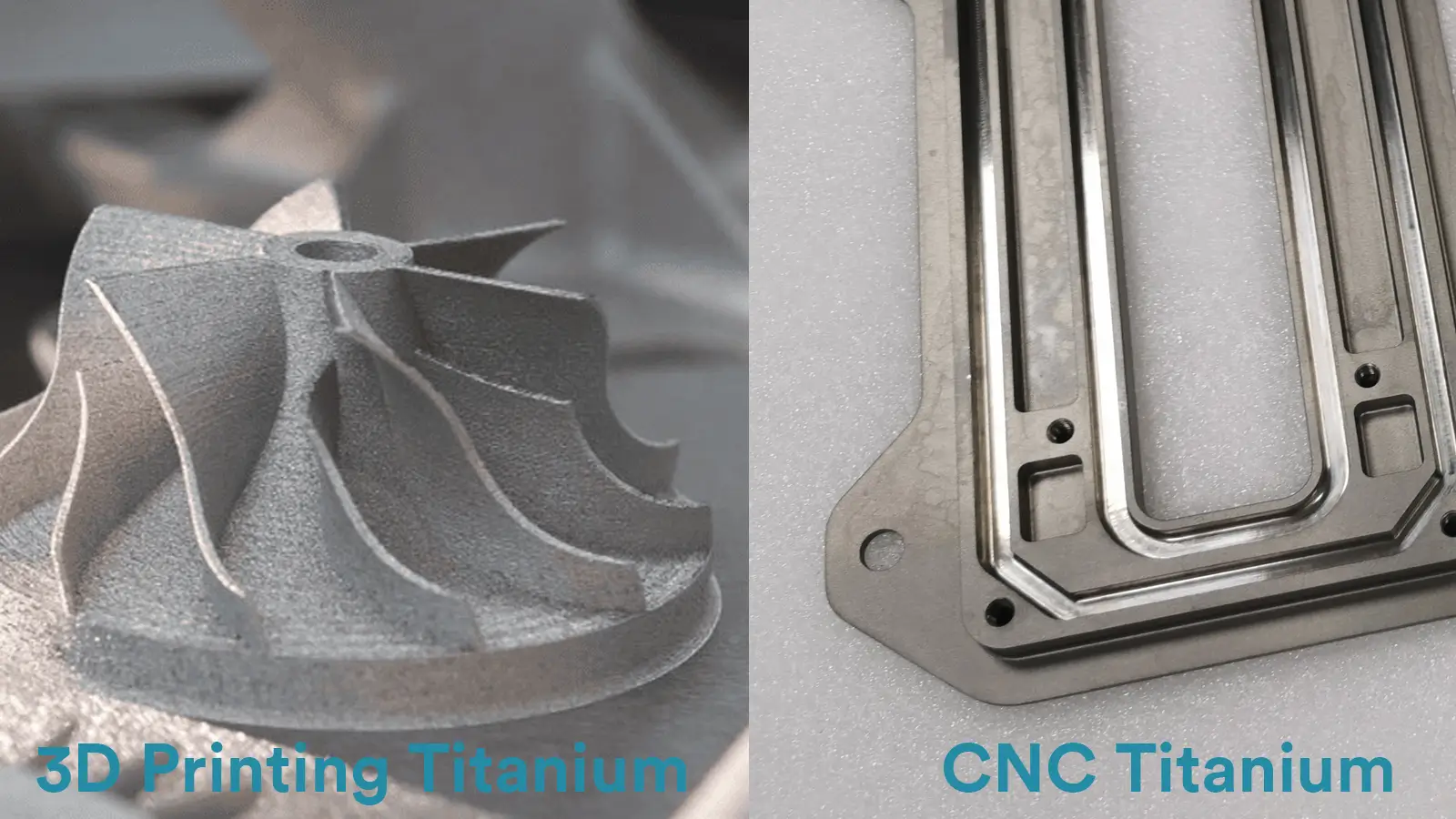

Titanium alloys are widely used in aerospace, medical, and high-end industrial applications—but manufacturing them is never straightforward. Between CNC machining and 3D printing, the trade-offs are not just about cost, but about precision, reliability, and long-term performance.

This article provides a side-by-side, experience-based comparison of CNC machining vs. 3D printing for titanium alloy parts. Instead of theory alone, we focus on what actually matters in real production: tolerances, surface quality, material integrity, lead time, and scalability.

1. CNC Machining of Titanium Parts

CNC machining titanium parts is a manufacturing process where a computer-controlled machine uses “subtractive” methods—like cutting, milling, drilling, or turning—to precisely shape a solid piece of titanium stock (such as a rod, plate, or forging) into the exact geometry and dimensions you need.

1.1 Key Features of CNC Machining Titanium

Material is Removed: The process takes away excess material with cutting tools—think of it like sculpting.

Digitally Programmed: Movements are guided by coded instructions (G-code/M-code).

Multi-Axis Capability: Using 3-, 4-, or 5-axis machines allows for creating complex curves and contours.

High Precision: Accuracy relies on the machine’s build quality and tool compensation systems.

1.2 Why Choosing CNC Machining for Your Titanium Parts?

For many mission-critical applications, CNC machining remains the “gold standard” due to its unmatched precision and material integrity.

Unrivaled Dimensional Accuracy

Precision Tolerances: We typically maintain tolerances between ±0.1mm and ±0.05 mm, with high-precision capabilities reaching as tight as ±0.002mm.

High-Fidelity Complex Features: Our 5-axis simultaneous machining can replicate any mathematically defined surface with absolute loyalty to your design.

Superior Surface Integrity

Excellent Surface Finish: Standard: Ra 0.8–1.6μm

Fine Finishing: Ra 0.2–0.4μm

Mirror Finishing: Ra <0.1μm (Ultra-precision)

Zero Metallurgical Defects: Unlike 3D printing, CNC machining eliminates concerns about internal porosity or “unmelted” layers. You get a solid, uniform part every time.

Consistent Performance: CNC parts are isotropic, meaning they maintain consistent strength in every direction, without the internal stress concentrations often found in additive processes.

Optimized Mechanical Properties

Uniform Strength: Consistent physical properties throughout the entire part.

Preserved Grain Structure: Our process retains the superior microstructure of forged or rolled titanium.

Thermal Control: We manage cutting heat to stay below the material’s recrystallization temperature, ensuring the metallurgical properties of your part remain intact.

1.3 Challenges in CNC Machining Titanium

While titanium is a “super material,” it is also notoriously difficult to work with. Based on our hands-on production experience, we navigate several unique challenges:

Heat Management: Titanium’s low thermal conductivity (approx. 7 W/m·K) means heat builds up at the tool’s edge rather than dissipating. Temperatures can exceed 1000°C, requiring expert cooling strategies.

High Cutting Forces: Titanium is 30–50% tougher than standard steel. This requires machines with significant power and high rigidity to ensure stability.

Chemical Reactivity: At high temperatures, titanium likes to “bond” with tool materials. Without the right coatings and parameters, tools can wear out rapidly due to diffusion and adhesion.

Elasticity & Vibration: Titanium’s lower modulus of elasticity means parts can “spring back” or vibrate during cutting. Our experts use specialized fixturing and tool paths to prevent this, ensuring your dimensions stay true.

Related blog:

Titanium CNC Machining Challenges and Cost Reduction Strategies

Cutting Tools for CNC Machining Titanium Alloy

2. 3D Printing of Titanium Parts

3D printing titanium parts is a digital manufacturing technology that builds objects layer by layer. It uses a high-energy beam (laser or electron beam) to selectively melt fine titanium alloy powder, directly transforming a 3D CAD model into a solid physical part.

We’ll now explore the main 3D printing methods for titanium.

2.1 Selective Laser Melting – SLM

SLM technology creates intricate titanium parts by using a high-power laser to meticulously melt micron-sized titanium powder, fusing it layer upon layer. The result is an extremely dense part with mechanical properties that rival those of traditional forgings.

2.1.1 The Standard SLM Production Workflow

Step 1: Data Preparation (Pre-processing)

3D Modeling: Design the part using CAD software.

Slicing: The 3D model is digitally sliced into thousands of ultra-thin layers (typically only about 0.03 mm thick each).

Support Generation: Because titanium experiences significant stress during melting, custom “support structures” must be designed. These anchors hold the part to the build plate and help dissipate heat.

Step 2: Machine Setup

Vacuum & Inert Gas: Titanium is highly reactive at high temperatures and can ignite or become brittle when exposed to oxygen. Therefore, the build chamber is first vacuumed and then filled with argon gas, reducing oxygen levels to an extremely low point (often below 100 ppm).

Pre-heating: The build plate is heated to a specific temperature to minimize thermal stress during the print.

Step 3: The Layer-by-Layer Build Process

Powder Recoating: A blade or roller spreads a perfectly even, thin layer of titanium powder (typically 20-50 microns thick) across the build platform.

Selective Melting: A high-power laser beam scans the powder bed, precisely melting and fusing the powder particles according to the cross-section of that specific layer.

Platform Lowering & Repeat: The build platform lowers by exactly one layer’s thickness. The process of recoating powder and laser scanning repeats.

Growth: After thousands of these cycles, a geometrically complex part “grows” from the powder bed.

Step 4: Post-Processing

Powder Removal: Once printing is complete, the part is carefully excavated from the surrounding loose powder.

Heat Treatment (Annealing): The printed part contains significant internal residual stress. It must undergo heat treatment in a vacuum furnace; otherwise, it could warp, distort, or even crack when removed from the build plate.

Support Removal & Detachment: The part is separated from the metal build plate using wire electrical discharge machining (EDM) or manual tools, and all support structures are removed.

Surface Finishing: Parts may undergo sandblasting, polishing, or even precision CNC machining on critical surfaces, depending on the final application requirements.

| Parameter | Typical Range | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Type | Fiber Laser (1070nm) | High beam quality, long lifespan |

| Spot Diameter | 50-150 μm | Fine feature resolution |

| Layer Thickness | 20-50 μm | High dimensional accuracy |

| Scan Speed | 500-2000 mm/s | High productivity |

| Build Volume | 250×250×300mm to 500×500×500mm | Industrial-scale parts |

| Oxygen Control | <100 ppm (often <30 ppm) | Prevents titanium oxidation |

2.1.2 Advantages and Disadvantages of SLM for Titanium

- Advantages of SLM Printing Titanium

Unprecedented Design Freedom:

Features that are prohibitively expensive with CNC machining—like complex internal channels, conformal cooling paths, and lightweight lattice structures—simply require a bit more print time with SLM.

It can create fine features like 0.3mm walls and 0.5mm holes, enabling topology-optimized parts that are 30-70% lighter without sacrificing strength. This is a game-changer for aerospace and motorsports.

Excellent Material Efficiency:

Titanium is expensive. SLM has a near-perfect “buy-to-fly ratio” (close to 1:1), saving up to 80% of costly raw material compared to machining from a solid block.

Superior As-Printed Properties:

The extremely small melt pool and rapid cooling result in a fine-grained microstructure. As-printed tensile strength often exceeds cast parts and can rival forgings.

Rapid Development Cycles:

No custom tooling or fixtures are needed. You can go from a CAD model to a holding a part in just days, drastically speeding up prototyping and iteration.

Part Consolidation:

Complex assemblies of dozens of components can often be redesigned as a single, integrated part. This eliminates the weight, potential failure points, and assembly time associated with welds and fasteners.

- Disadvantages of SLM Printing Titanium

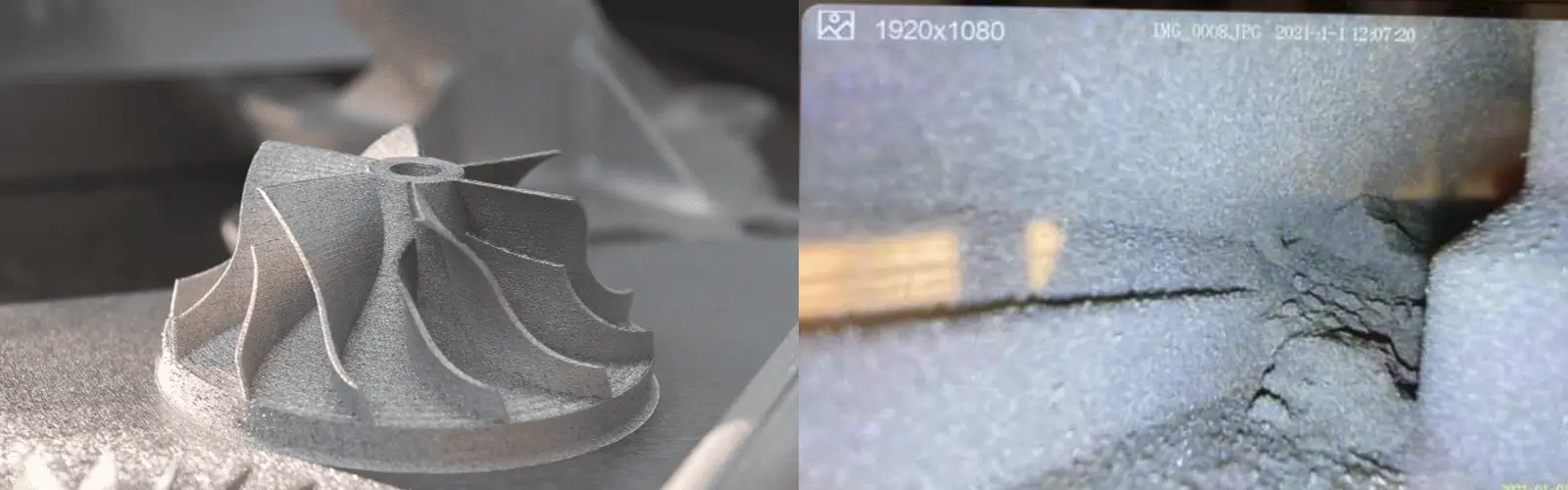

High Residual Stress:

This is SLM’s main challenge. Extreme temperature gradients create significant internal tensile stress. Without proper process control and post-processing, parts can warp, distort, or crack.

Surface Roughness:

While dimensionally accurate, the as-printed surface has a characteristic “grainy” texture from partially sintered powder (Ra ~5-15 μm). Critical bearing or sealing surfaces almost always require secondary machining.

Anisotropy:

Due to the layer-wise build process, mechanical properties in the vertical (Z-axis/build) direction are typically slightly lower than in the horizontal planes.

Size Limitations:

Part size is constrained by the powder bed dimensions and laser scan range. Mainstream SLM machines struggle with single parts exceeding 600-800mm.

Complex & Costly Post-Processing:

The job isn’t done when the print finishes. Post-processing often requires expensive vacuum heat treatment, wire EDM, sandblasting, and sometimes Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) to close internal pores.

2.2 EBM 3D Printing

Unlike SLM’s laser, EBM (Electron Beam Melting) uses a high-energy electron beam as its heat source, and the entire process occurs in a high-temperature vacuum.

Key Advantage:

The part sits on a “hot bed” (around 700°C or higher) throughout the build. This drastically reduces residual stress in titanium. EBM parts typically don’t require complex stress-relief annealing and are less prone to cracking.

Typical Application:

It’s often the preferred choice for medical implants (like artificial hip joints) because its slightly rougher surface texture actually promotes better bone cell attachment and growth.

2.3 DED

The full name of DED is Directed Energy Deposition.

LMD’s full name is Laser Metal Deposition.

Think of this technology as a high-end “welding robot” that can simultaneously feed and melt metal powder or wire. It deposits material where needed.

Key Advantage:

Excellent for very large parts and high deposition rates. It isn’t limited by a powder bed, making it suitable for multi-meter aerospace components or for repairing damaged high-value titanium parts.

Typical Application:

Large aircraft structural frames and repair of turbine blades or other engine components.

2.4 WAAM

The full name WAAM is Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing.

This process essentially combines automated welding with 3D printing, using titanium wire as the feedstock melted by an electric arc.

Key Advantage:

Very low cost and extremely high build speed. Titanium wire is significantly cheaper than powder, and deposition rates are immense.

The trade-off is lower accuracy and a rough, wavy surface (often likened to “lava cake”), necessitating extensive subsequent CNC machining.

Typical Application:

Large, near-net-shape aerospace components where final precision will be achieved via machining (e.g., pylon mounts, fuel tank brackets).

2.5 Binder Jetting

This method doesn’t use a laser to melt. Instead, it operates like an inkjet printer, spraying a liquid binding agent onto a bed of titanium powder to “glue” the shape layer by layer. The “green” part is then sintered in a high-temperature furnace.

Key Advantage:

The fastest potential method, ideal for batch production. Since it doesn’t rely on point-by-point laser scanning, it can print entire layers nearly instantly.

Current Challenge:

Titanium experiences significant shrinkage during sintering and is extremely sensitive to oxygen. Application for high-performance titanium parts is still an area of active development and process refinement.

Comparison of 3D Printing Technologies for Titanium Alloys

| Aspect | SLM | EBM | DED | Binder Jetting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | ★★★★★ | ★★★☆☆ | ★★☆☆☆ | ★★★★☆ |

| Surface Finish | ★★★★☆ | ★★☆☆☆ | ★★☆☆☆ | ★★★☆☆ |

| Build Speed | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★★☆ | ★★★★★ | ★★★★★ |

| Material Quality | ★★★★★ | ★★★★☆ | ★★★☆☆ | ★★☆☆☆ |

| System Cost | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★★☆ | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★★★ |

| Ease of Use | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★★☆ | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★★★ |

| Industry Adoption | ★★★★★ | ★★★☆☆ | ★★☆☆☆ | ★★☆☆☆ |

While SLM isn’t the best at everything, it shines where it really counts: precision, quality, reliability, and overall maturity. That’s why it’s become the go-to choice for most high-performance titanium parts—it’s a technology that’s been refined and trusted over nearly 20 years of real-world use.

Looking ahead, as SLM systems become more accessible and cost-effective, we expect to see them used in even more applications. Still, for the next 5–10 years, SLM is likely to remain the top choice whenever accuracy, surface quality, and dependability are non-negotiable.

If you’re working on something that demands high precision and reliable material properties, SLM continues to be a smart, proven option.

3. Forging Titanium Alloy Parts

Forging is a process that shapes titanium alloy through plastic deformation rather than adding or removing material.

In simple terms, a titanium workpiece is heated until it’s glowing hot (around 800–1100°C) and then pressed into a mold under immense pressure (equivalent to dozens or even hundreds of atmospheres). This not only forms the part but also significantly enhances its material properties.

3.1 Key Strengths of Forged Titanium

Unmatched Strength and Durability

If your part needs to withstand repeated high-stress impacts—like an aircraft landing gear hitting the runway—forged titanium is often the most reliable choice. It offers exceptional fatigue resistance and toughness, outperforming most other manufacturing methods.

We Can Align Its “Grain”

Similar to wood grain, metal has an internal microstructure. During forging, we can intentionally align this grain along the part’s main stress directions, giving it extra strength exactly where it’s needed most.

Uniform and Trustworthy Internal Quality

Forged parts have a consistent, dense internal structure, free from hidden defects like the porosity sometimes found in castings or the layer-related flaws that can occur in 3D-printed parts. This makes them a safe and dependable option for critical applications.

3.2 Limitations of Forged Titanium

Simpler Shapes

Forging generally produces relatively basic forms—often called “blanks” or “near-net shapes.” It’s not well-suited for creating intricate internal channels, fine threads, or thin-walled features directly.

Almost Always Requires CNC Machining Afterwards

As-forged surfaces are rough and dimensional accuracy is limited, so subsequent CNC machining is almost always necessary to achieve the final precision and surface finish required.

Higher Cost, Best for Larger Batches

The process requires expensive custom molds (often costing tens of thousands of dollars) and massive presses (weighing thousands of tons), making it most economical for medium- to high-volume production runs.

4. CNC Machining vs. 3D Printing for Titanium Parts

Having looked at different ways to make titanium parts, let’s now focus on the two leading methods in today’s market: CNC machining and 3D printing—especially SLM 3D printing.

Here’s a friendly, side-by-side comparison to help you understand where each one shines.

4.1 Design Freedom

| CNC Machining | 3D Printing (SLM) |

|---|---|

| Has clear limits due to the physical reach and movement of cutting tools. It struggles with enclosed internal cavities, extremely complex porous structures, or embedded channels. Parts often need to be split into multiple components and assembled later. | Offers exceptional freedom. It can create geometries impossible with traditional methods—like internal cooling channels, lightweight lattice structures, and fully integrated assemblies—all in one piece. The main design rules relate to printability (like overhang angles and support needs). |

4.2 Material Efficiency

| CNC Machining | 3D Printing (SLM) |

|---|---|

| Generally low material efficiency—only 10–30% of the starting block ends up in the final part. For complex shapes, the “buy-to-fly” ratio can be as high as 10:1, meaning a lot of expensive titanium ends up as chips. | Highly material efficient, often over 90%. It melts powder only where the part is, and unused powder can be recycled. This saves a lot of costly titanium, especially for intricate designs. |

4.3 Lead Time for Prototypes & Small Batches

| CNC Machining | 3D Printing (SLM) |

|---|---|

| Longer setup time for new parts: programming, fixture design, and toolpath optimization can take days or even weeks before cutting starts. Not ideal for fast iteration. | Much faster from file to part—no custom fixtures needed. Preparation mainly involves slicing the model and generating supports, often done in hours. Great for rapid prototyping and quick design revisions. |

4.4 Dimensional Accuracy & Tolerances

| CNC Machining | 3D Printing (SLM) |

|---|---|

| Industry-leading precision, capable of ±0.002 mm or better. Reliable and predictable, ideal for tight-tolerance assembly fits. Accuracy depends on machine quality and tool compensation. | Good accuracy, typically around ±0.1 mm. Influenced by thermal effects, support design, powder quality, and scanning strategy. Critical mating surfaces usually need machining afterward for final precision. |

4.5 Surface Quality

| CNC Machining | 3D Printing (SLM) |

|---|---|

| Excellent surface finish right off the machine—can achieve Ra 0.4–0.8 μm with fine finishing, and mirror-like polish (Ra <0.1 μm) when needed. Suitable for sealing surfaces, bearing fits, and high-fatigue applications. | As-printed surfaces are rough (Ra 5–15 μm) with a “grainy” texture from layer lines and partially fused powder. Functional surfaces require secondary machining or polishing. |

4.6 Material & Mechanical Properties

| CNC Machining | 3D Printing (SLM) |

|---|---|

| Preserves the original titanium properties—excellent strength, toughness, fatigue resistance, and isotropic behavior (same in all directions). Residual stress is minimal after stress relief. | Good static strength, often matching forgings, but slightly anisotropic (weaker in the build direction). Contains internal stress that requires heat treatment, and may have tiny pores that sometimes need hot isostatic pressing (HIP). |

4.7 Cost & Economics

| CNC Machining | 3D Printing (SLM) |

|---|---|

| Cost-effective at high volumes: upfront programming and fixture costs are spread over many parts. Per-part cost drops significantly in mass production. Main costs: machine time, labor, tool wear, and material waste. | Cost-effective for low volumes and prototypes: no molds or special fixtures needed. But per-part cost doesn’t drop much at high volumes because each part still takes similar print and post-processing time. Main costs: machine investment, high-purity powder, inert gas, and post-processing. |

5. How to Choose: CNC Machining vs. 3D Printing for Titanium Alloy Parts

Stuck deciding between CNC and 3D printing? Here’s a straightforward guide to help you choose the best path.

✅ When to Lean Toward 3D Printing (SLM)

Consider 3D printing first if any of these sound like your situation:

You need extreme lightweighting:

Parts that require topology optimization to cut non-critical weight (30–70% lighter), like aerospace brackets or racing components.

You want part consolidation:

Combine multiple parts that would normally be welded, bolted, or assembled into a single, integrated piece—reducing assembly steps and potential failure points.

You need biocompatible or functional structures:

Think medical implants with porous surfaces for bone integration—designs that are tough or impossible to do with CNC alone.

Material is very expensive and geometry is complex: When the cost of CNC waste (“buy-to-fly” ratio) outweighs the total cost of printing, 3D printing becomes the smarter financial choice.

You’re in rapid prototyping or iteration mode: You need a physical part in days to test form, fit, or function.

✅ When to Lean Toward CNC Machining

CNC is likely the better route if any of these are top priorities:

You need high precision and superior surface finish:

For bearing seats, sealing surfaces, threads, or cosmetic surfaces—where tolerances are tighter than ±0.1 mm and surface roughness needs to be below Ra 1.6 μm.

Material performance is critical:

Parts must have isotropic strength, maximum fatigue resistance, and long-term reliability—think jet engine components or landing gear structures.

You’re moving into medium- to high-volume production:

Once the design is finalized and geometry is machinable, CNC becomes highly cost-effective and efficient for batches (typically >100 pieces).

The part is simple to moderately complex with regular features:

No internal channels or extreme geometries that a cutting tool can’t reach.

6. Summary

A phased decision-making process often works best:

Prototyping & Design Validation: Start with 3D printing for speed and flexibility.

Low-Volume Pilot Production: Evaluate pure 3D printing, pure CNC, or hybrid based on part complexity, performance needs, and cost.

Full-Scale Production: Optimize for cost—CNC for simpler geometries, hybrid or optimized 3D printing for complex ones.

While 3D printing continues to improve and become more accessible, CNC machining remains essential where extreme precision, reliability, and volume efficiency are non-negotiable.

⚠️ Safety Notice

The processes described involve high temperatures, high pressures, inert gases, and flammable metal powders. All work must be carried out by trained professionals following appropriate safety protocols and protective measures.

Lucas is a technical writer at ECOREPRAP. He has eight years of CNC programming and operating experience, including five-axis programming. He’s a lifelong learner who loves sharing his expertise.

Other Articles You Might Enjoy

What is 5-axis Machining? A Complete Guide.

5-Axis CNC machining is a manufacturing process that uses computer numerical control systems to operate 5-axis CNC machines capable of moving a cutting tool or a workpiece along five distinct axes simultaneously.

Which Country is Best for CNC Machining?

China is the best country for CNC machining service considering cost, precision, logistic and other factors. Statistical data suggests that China emerges as the premier destination for CNC machining.

Top 5 Prototype Manufacturing China

Selecting the right prototype manufacturing supplier in China is a critical decision that can significantly impact the success of your product development project.

CNC Machining Tolerances Guide

Machining tolerances stand for the precision of manufacturing processes and products. The lower the values of machining tolerances are, the higher the accuracy level would be.