Table of Contents

In modern precision CNC machining, titanium alloys are considered true “star materials.” Due to their exceptional strength-to-weight ratio and outstanding corrosion resistance, they are indispensable in aerospace, medical implants, and high-end industrial applications.

But for CNC engineers, titanium alloys are also famously “difficult to work with.” Its low thermal conductivity, high chemical reactivity, and unique physical properties make the machining process a high-stakes balancing act—akin to dancing on the edge of a cutting tool.

Drawing on more than ten years of hands-on experience, this article breaks down the real challenges behind titanium CNC machining and explains how manufacturers can maintain quality while keeping notoriously high machining costs under control.

Key Takeaways:

Titanium is difficult to machine because heat builds up at the cutting edge, tools wear rapidly, and the material deflects and work-hardens under load.

High chemical reactivity of titanium causes built-up edge, unstable cutting, and poor surface finish, making process control critical.

Short tool life, long cycle times, and expensive tooling and materials are the main drivers of titanium machining cost.

Cost control depends on smart design, optimized CAM strategies, proper tooling and cooling, and experienced process planning—not shortcuts.

1. Why Is Titanium CNC Machining Difficult?

Titanium alloys are widely known as difficult-to-machine materials.

From a manufacturing engineering perspective, the complexity and cost of CNC machining titanium are mainly driven by three interrelated risks that are hard to control: heat, force, and chemical reactivity.

The key challenges can be summarized as follows.

1.1 Low Thermal Conductivity

This is the most critical issue.

Titanium alloys have extremely low thermal conductivity—roughly one-sixth of steel and only one-sixteenth of aluminum, and that is why it has poor heat dissipation.

What does this mean in real machining conditions? The heat generated during cutting cannot be efficiently carried away by the chips or the workpiece.

Instead, it concentrates intensely at the cutting edge and the machined surface, leading to several serious problems:

- Rapid tool wear

Under high temperatures, the cutting edge softens quickly and undergoes chemical reactions with titanium, dramatically shortening tool life.

- Thermal damage to the workpiece

Localized overheating can cause surface hardening, micro-cracks, or even changes in the material’s microstructure, negatively affecting fatigue strength and overall part integrity.

1.2 High Chemical Reactivity

At elevated temperatures (around 500°C and above), titanium readily reacts with nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen in the air—as well as with tool materials themselves, especially the cobalt binder found in carbide tools.

This high reactivity causes chips to easily weld or adhere to the cutting edge, forming what is known as a built-up edge (BUE).

The consequences are significant:

The tool geometry is damaged, resulting in unstable cutting conditions

Torn surfaces, burrs, and poor surface finish appear on the machined part

More specifically:

- Reaction with oxygen and nitrogen

Titanium forms extremely hard compounds such as TiO₂ and TiN at high temperatures. These layers—often referred to as an alpha-case brittle layer—increase abrasive wear on both the tool and chips.

- Reaction with hydrogen

This can lead to hydrogen embrittlement, reducing local ductility.

- Reaction with tool materials

This is the direct chemical cause of “tool sticking.” Titanium atoms diffuse and alloy with cobalt (Co) in WC/Co carbide tools, creating microscopic “weld points” at the tool–chip interface.

Because of these reactions under high temperature and pressure, the friction between the chip and the rake face of the tool becomes extremely high. Portions of the titanium chip are literally torn off and firmly adhere to the cutting edge.

As these deposits accumulate and harden, a built-up edge forms—accelerating wear and degrading machining stability.

1.3 Low Elastic Modulus

Titanium alloys have a relatively low elastic modulus—about half that of steel.

It has poor rigidity. Under the cutting forces, the workpiece is more prone to elastic deformation and vibration, leading to the well-known “tool deflection” or “spring-back” effect.

This results in:

- Difficulty maintaining dimensional accuracy

The part deflects during cutting and rebounds after the tool passes, making it difficult to achieve tight tolerances.

- Nightmare scenarios for thin-wall parts

Thin-walled or complex structures are especially susceptible to chatter, distortion, and even scrapping.

- Poor surface finish

Vibration directly reduces surface quality.

1.4 High Strength & Work Hardening Tendency

In addition, titanium alloys retain high strength even at elevated temperatures and exhibit a strong tendency toward work hardening.

During cutting, the material beneath the tool rapidly hardens due to severe plastic deformation.

Subsequent tool passes must cut through an even harder and more wear-resistant layer, which further accelerates tool wear and increases machining difficulty.

In summary, the machining difficulty of titanium stems from concentrated cutting heat, strong tool–material chemical interaction, low elastic modulus, and severe work hardening.

2. Five Common Problems in Titanium CNC Machining

Based on over a decade of hands-on experience machining titanium alloys, we consistently see the following challenges during titanium CNC machining.

2.1 Extremely Short Tool Life

During titanium machining, cutting heat is highly concentrated at the tool edge. Under sustained high temperatures, the cutting edge quickly softens, oxidizes, and suffers diffusion wear.

As a result, tool life can be as low as only 20–30% of what you would expect when machining steel. Frequent tool changes become unavoidable, driving tooling costs sharply higher and reducing overall machining efficiency.

2.2 Severe Built-Up Edge and Poor Surface Control

Titanium alloys are highly chemically reactive and tend to bond with tool materials at elevated temperatures. Chips can literally “weld” to the cutting edge, forming a built-up edge (BUE).

This built-up material changes the tool’s effective cutting geometry and often triggers vibration.

When the BUE periodically breaks away, it tears the machined surface, leaving burrs, rough textures, and visible surface damage.

In many cases, the detached BUE can also pull away tool coatings—or even small portions of the tool substrate—leading to microchipping and groove wear, which further shortens tool life and makes surface quality difficult to control.

2.3 Low Rigidity, Easy Deformation, and Tolerance Issues

When CNC machining titanium alloys, tool deflection—often referred to as “tool push-back”—is a common problem. With a low elastic modulus of around 110 GPa (about half that of steel), titanium lacks stiffness.

Under cutting forces, the workpiece elastically deforms and then springs back once the tool passes, making tight dimensional tolerances difficult to maintain.

This issue becomes especially severe when machining thin-walled or complex titanium parts, where chatter, distortion, and even part rejection are frequent risks.

To compensate, manufacturers often rely on complex fixturing, additional support, and multiple light cutting passes—significantly reducing process efficiency.

2.4 Strong Work-Hardening Tendency

Titanium alloys are highly prone to work hardening in the plastic deformation zone.

The hardness of the machined surface increases noticeably after each pass, meaning the next tool path is effectively cutting into a harder, more wear-resistant layer.

If the depth of cut is too small, the tool may end up rubbing rather than cutting the hardened surface.

This dramatically increases heat generation, accelerates tool wear, and further complicates subsequent machining operations.

2.5 High Cost and a Very Narrow Process Window

High tooling costs, long cycle times, and expensive raw material all contribute to the high overall cost of titanium CNC machining.

At the same time, titanium offers a very narrow process window—small deviations in cutting parameters, tool condition, or cooling strategy can quickly lead to tool failure, poor surface quality, or scrapped parts.

Controlling cost while maintaining quality therefore requires deep process knowledge and precise execution.

3. Key Factors That Drive the Cost of Titanium CNC Machining

The machining difficulty of titanium alloys directly translates into high manufacturing costs. In practice, the cost of titanium CNC machining is driven by several key factors.

3.1 High Cutting Tooling Cost

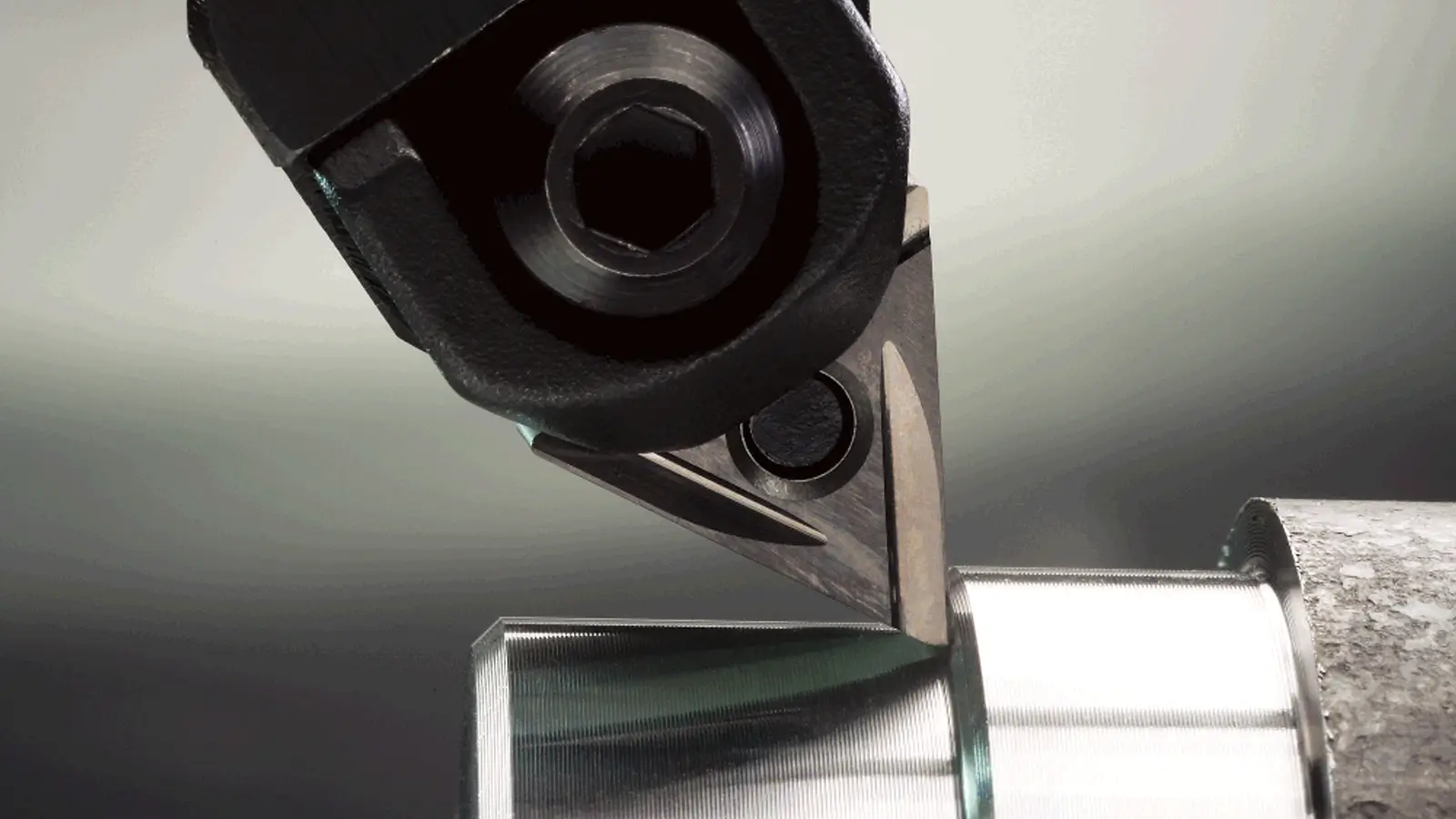

Machining titanium alloys requires high-performance cutting tools—such as ultra-fine grain carbide tools, advanced PVD-coated tools (e.g., TiAlN), or even polycrystalline diamond (PCD) tools in certain applications. These tools are inherently expensive.

On top of that, tool life in titanium machining is significantly shorter than when cutting steel or aluminum.

Frequent tool changes are unavoidable, making tooling consumption one of the biggest cost contributors.

Some titanium components also require specialized tool geometries, such as larger rake angles and very sharp cutting edges, to reduce cutting forces and improve chip evacuation. These custom or application-specific tools further increase overall cost.

3.2 Machining Time and Process Strategy

To prevent excessive heat buildup and premature tool failure, titanium milling and turning must be performed at relatively low cutting speeds, with moderate feed rates and shallow depths of cut.

As a result, the material removal rate is low, and machining cycles become significantly longer.

Because of titanium’s low rigidity, machining often requires more complex and precise fixturing to properly support the workpiece and suppress vibration.

For complex geometries, five-axis CNC machines are commonly used to access features from multiple orientations—equipment that carries a higher hourly rate.

Titanium machining programs typically involve multiple cutting passes to gradually remove work-hardened layers. In some cases, stress relief or heat treatment steps are inserted between roughing and finishing operations to maintain dimensional stability.

Titanium CNC machining also places extremely high demands on process planning and CAM programming experience. The process is highly sensitive to operation sequencing, cutting parameters, toolpath strategy, fixturing methods, and deformation control.

Engineers must carefully distribute machining allowances across roughing, semi-finishing, and finishing stages, manage cutting forces and heat concentration, and rely on experience to select appropriate tools, tool overhang, entry/exit strategies, and stable, continuous toolpaths in CAM.

A lack of experience often leads to chatter, part distortion, dimensional inaccuracies, or rapid tool failure—significantly increasing scrap rates, extending lead times, and ultimately making costs difficult to control.

3.3 Demands on Machine Performance & Rigidity

Titanium machining places high demands on machine performance, requiring excellent static and dynamic rigidity (from heavy-duty beds and robust structures), ample low-to-mid-range torque (for efficient roughing), and high motion accuracy and stability.

As a result, shops often need high-rigidity CNC machines, high-torque spindles, and stable multi-axis systems—all of which come at a higher capital cost.

3.4 Auxiliary Systems and Consumables

Effective titanium machining requires high-pressure, high-flow coolant systems that deliver coolant directly to the cutting edge to aggressively remove heat and evacuate chips. These systems—along with specialized oil-based or synthetic coolants—add to operating costs.

Titanium parts, especially for aerospace applications, often require 100% non-destructive testing (NDT) such as fluorescent penetrant inspection or X-ray inspection.

Post-processing steps like deburring and polishing are also more difficult and time-consuming than with most other materials.

3.5 Titanium Raw Material Cost

Titanium alloy raw materials—such as Ti-6Al-4V (TC4) bars and plates—are expensive to begin with, making material cost itself a significant portion of the total.

In short, titanium CNC machining is difficult because of its contradictory material behavior—it is “strong yet flexible, sticky yet brittle, and highly resistant to heat flow.”

The high cost comes from rapid tool wear, long machining cycles, mandatory high-end auxiliary systems, and expensive raw materials.

Successfully machining titanium requires a combination of deep process knowledge, advanced equipment, and disciplined execution—which is ultimately why titanium components command a premium price.

4. How to Reduce the Cost of Titanium CNC Machining?

Reducing the cost of titanium CNC machining is not about cutting corners—it’s about making smarter decisions across design, material selection, process planning, and production strategy.

4.1 Optimize Part Design (Design for Manufacturability)

4.1.1 Increase fillet radii

Avoid sharp internal corners whenever possible. Larger fillet radii allow the use of larger-diameter, more rigid tools, enabling higher cutting speeds while reducing the risk of tool breakage.

4.1.2 Simplify thin-wall features

Titanium has strong elastic recovery. When wall thickness drops below about 1 mm, machining requires extremely low feed rates to avoid chatter. Increasing wall thickness significantly improves stability and machining efficiency.

4.1.3 Minimize deep-hole machining

Deep holes (depth greater than 4× the diameter) are especially challenging in titanium due to poor chip evacuation and severe heat buildup. Whenever possible, shorten hole depth or redesign the feature as a through-hole.

4.1.4 Avoid unnecessary ultra-tight tolerances

Define tolerances and surface finishes based on actual functional requirements. Relaxing tolerances on non-critical surfaces can dramatically improve machining efficiency and reduce cost.

4.2 Select the Right Titanium Grade

Use Ti-6Al-4V ELI (Extra Low Interstitial) only when it is truly required. If Grade 2 commercially pure titanium or standard Grade 5 titanium meets the strength and performance requirements, both material cost and machining difficulty will be significantly lower.

Visit Titanium Grades and Alloys for more information.

4.3 Optimize Machining Processes and Strategies

4.3.1 Refined tooling strategy

Select the most cost-effective tools for each machining stage—roughing, semi-finishing, and finishing. Tough, general-purpose grades work well for roughing, while high-performance coated tools are reserved for finishing.

Tool life should be defined based on data and experience to avoid changing tools too early (wasteful) or too late (risking catastrophic part scrap).

4.3.2 CAM Programming Optimization

- Dynamic milling / trochoidal milling

Maintains a constant tool load with shallow axial depth and higher feed rates, enabling high material removal rates while reducing heat, vibration, and tool wear.

- High-speed machining

When machine and tooling allow, higher spindle speeds and feeds can actually reduce heat accumulation, shorten cycle time, and sometimes even extend tool life.

Toolpath optimization

Minimize air cuts and keep toolpaths smooth and continuous. Leverage machine look-ahead and high-speed smoothing functions to fully utilize machine dynamics.

- Simulation and verification

Use CAM simulation for cutting force analysis and collision detection to prevent crashes, broken tools, and scrapped parts caused by programming errors.

4.3.2 Maximize the Effectiveness of the Cooling System

- Ensure high-pressure coolant is truly effective

Regularly check nozzles for blockage and verify that pressure meets requirements. Delivering coolant precisely and forcefully into the cutting zone is one of the most effective ways to reduce tool wear.

- Coolant maintenance

Keep coolant clean and concentration stable to prevent bacterial growth and loss of lubrication performance. This indirectly improves surface finish and extends tool life.

4.4 Batch Planning and Production Optimization

Titanium setups and first-article validation are time-consuming. Group parts made from the same material and condition into the same production batch to minimize changeovers, reprogramming, and machine setup time.

Running titanium parts in larger batches allows fixed costs to be spread across more parts, significantly reducing the per-piece cost.

Titanium CNC Machining Cost-Reduction Strategy Overview

| Stage | Core Strategy | Key Actions | Expected Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Simplify & optimize | DFM review, near-net-shape blanks | Less machining, lower material waste |

| Process | Maximize efficiency | Dynamic milling, optimized toolpaths, high-pressure coolant | Shorter cycle time, longer tool life |

| Tooling | Fine control | Tool tiering, tool life management | Lower tooling consumption |

| Operations | Efficient resource use | Batch production, automation | Higher machine utilization, lower fixed cost per part |

5. Summary

The key to reducing titanium CNC machining cost lies in systematic optimization across design, process planning, programming, and overall manufacturing strategy.

Cost savings start at the design stage by eliminating unnecessary tight tolerances and overly thin structures.

During machining, stable and efficient cutting strategies—such as dynamic milling, balanced stock allowance across roughing and finishing, and consistent tool engagement—help extend tool life and shorten cycle time.

In addition, the right tool coatings, effective high-pressure cooling, controlled tool overhang, and machines with sufficient rigidity and torque all play a critical role in reducing vibration and thermal damage.

When combined with experienced engineers who can fine-tune CAM toolpaths and cutting parameters, scrap rates drop, rework is minimized, and overall machining cost can be effectively controlled—without compromising part quality.

Lucas is a technical writer at ECOREPRAP. He has eight years of CNC programming and operating experience, including five-axis programming. He’s a lifelong learner who loves sharing his expertise.

Other Articles You Might Enjoy

What is 5-axis Machining? A Complete Guide.

5-Axis CNC machining is a manufacturing process that uses computer numerical control systems to operate 5-axis CNC machines capable of moving a cutting tool or a workpiece along five distinct axes simultaneously.

Which Country is Best for CNC Machining?

China is the best country for CNC machining service considering cost, precision, logistic and other factors. Statistical data suggests that China emerges as the premier destination for CNC machining.

Top 5 Prototype Manufacturing China

Selecting the right prototype manufacturing supplier in China is a critical decision that can significantly impact the success of your product development project.

CNC Machining Tolerances Guide

Machining tolerances stand for the precision of manufacturing processes and products. The lower the values of machining tolerances are, the higher the accuracy level would be.